|

HE AIN'T HEAVY

6/7/2018

This afternoon I found the most amazing message on my answering machine! (I am an unapologetically analog-type Luddite. I have an answering machine. I do not own a smart phone. I have never downloaded an app of any sort. Fear me or pity me...)

The call was from a stranger in Louisiana who said he was trying to get in touch with the family of a Mr. Wayne Hyde. He said he was the son of a soldier whose life Wayne had saved during World War 2, and he hoped to communicate with the man who'd rescued his dad 74 years ago, if that was still possible.He left his number, and an invitation to call him if I could spare the time to talk for a few minutes.

My father-- Wayne Hyde -- was an Airborne Ranger-- a paratrooper. Pop fought in the Battle Of The Bulge, in the Ardennes Forest of Belgium. It was a hideous clash--the largest battle ever fought by the US Army, and the most intense and costly combat of the entire war in Europe. If you're not familiar with the details, Google it and prepare to go slack-jawed. Just... unimaginable carnage on an epic scale.

I phoned the man, and in a few seconds of conversation, established that he was sincere, legit, and correct. He knew details about my father's background and anecdotal info about my family that could only have come from Pop. His dad-- Hector Aguiluz ("AG-ih-looz")-- and mine had been in the same Ranger outfit-- I Company, 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment, of the 17th Airborne Division-- and they'd entered the European combat theater by (as Pop always put it) "...jumping out of perfectly good airplanes" into Holland, and fighting their way thru Luxembourg and into Belgium. Paratroopers were THE elite troops back then, and the Airborne tended to attract some pretty rough, cocky guys.

My father, quite the young hellion --and a seriously delinquent, reform school and foster-home raised kid-- often spoke of his early days in "Jump School"-- Parachute Infantry training-- and told these insane stories of some wild times and very dangerous and marginal behavior. One story featured him and a few other troopers drunkenly hopping a freight train to get somewhere, and when they realized it wasn't actually going where they needed to be, they simply lined up and bailed out-- jumping in parachute formation from the open boxcar door of the speeding train and tumbling out into a field. "Today you'd say we all 'stuck the landing', I guess", he told me, laughing about it. Brawling and macho hooliganism were rampant. Discipline was kind of randomly applied, and a lot of these guys were real troublemakers.

The 513th PIR was a recently formed, green outfit, and were apparently kind of a problem to control. They were hurriedly trained, sparsely equipped, and double-time rushed into combat both because of the urgent need for reinforcements in the Ardennes region around Bastogne, and partially to get them the hell out of their training camp and to put all that psychotic energy to work doing something constructive. Like... well, killing Nazis.

So... during the worst European winter in human memory, December, 1944, a huge battle kicks off along a 50 mile long, 70 mile deep area in the American lines in this dense, frozen Belgian Ardennes Forest, ultimately involving 190,000 (One Hundred Ninety Thousand...) combined casualties. Let that sink in for a moment. In early January, a small scouting party is sent to scope out the situation and report back on enemy troop strength and vehicular movements-- gathering any useful intelligence they can.

Crossing a field, they are fired upon by German machine gunners. Most are killed instantly; one is shot and badly wounded. He lies still in the snow, playing dead. The nearby murders of 84 unarmed, captive, American soldiers by SS Panzer troops in the very recent Malmedy Massacre had most American GI's convinced that they'd be automatically killed rather than taken alive, should they fall, wounded in action.

He lay there, freezing and bleeding for nearly eleven hours, afraid to move, as he heard activity around him. Some time after dusk, passing in and out of consciousness, he heard a scrabbling sound in the snow nearby and raised his head enough to see an American paratrooper creeping toward him. This fellow sees he's alive, and lifts him onto his shoulders and carries him back, running most of the way, to the American lines and safety.

This fellow Ranger had gone out behind enemy lines (and, it turns out, against direct orders looking for the scouts who'd failed to return to camp after several hours.

That wounded scout was Hector Aguiluz. The Ranger who found him and carried him back was my dad. My father had made the rank of Sergeant, and was ultimately busted down, stripped of it and ended his service at the rank of Corporal for this-- but he got that guy out alive. His Regiment took huge casualties, and at least a couple of 513th troopers earned Congressional Medals of Honor, while the Regiment collectively earned a Presidential Unit Citation for extraordinary heroism in action. One of his fellow Rangers was J.D. Tippit, who years later, as a Dallas policeman, would be murdered by Lee Harvey Oswald. (The world just got much smaller for me when I learned this...)

Pop himself received 2 Purple Hearts for his wounds. He was eventually shot up so badly he was evacuated from the Ardennes to an aid station where he was stabilized and shipped home. He spent months in Army hospitals, in one of which he met the young woman who would become my mother-- an Army nurse. He was also awarded the Bronze Star medal-- for "heroic or meritorious achievement or service", and a Silver Star medal-- for "a singular act of gallantry, valor or heroism against an enemy", and he had been recommended for the even higher award, the Distinguished Service Cross.

None of these decorations had *anything* to do with him retrieving this wounded comrade.

Hector Aguiluz-- like my own father-- rarely spoke about his wartime experiences. The two men became friends and corresponded for many years after the war. Hector's son told me that his dad often read him my father's letters, and shared with him the recordings Pop sent him of his days as a musician and vocalist with Swing bands.

In 1989, Pop gave me a small cardboard box containing his old uniform patches, insignia, campaign badges and service decorations-- ribbons and pins and medals. I asked him to explain to me the history or significance of these items, as some were semi-familiar while others were complete mysteries. For all his love of the Paratroops, his pride in the Rangers, respect for the military-- and the stories of the crazy shit he and his buddies pulled-- he'd never wanted to speak about actual combat. A few days later he handed me an envelope, which I still have.

For the first time ever, he opened up to me about his life that horrible Winter of '44-'45, detailing his movements during the Battle Of The Bulge. The circumstances surrounding the reason he was given those medals-- and some of the horrifying stories they represented-- took four typewritten pages to lay out, and when I finished reading them, I had a new and stupefying picture of this giant, this superhero-- a man who so ironically appeared as a frail, elderly guy you'd never glance at twice on the street. Holy shit, man! Unbelievable, what he'd been through and survived. By comparison, my life has been one long, catered picnic in the countryside... with security guards, insect repellent and piped-in Muzak.

He never told me this particular story, though-- possibly because it cost him a demotion, or it broke protocol... I don't know. This was the first I heard of it. Hector lost all his saved letters and tapes and photos from Pop during Hurricane Katrina, and they eventually fell out of touch. He died in 2005, the same year as Pop did, both men in their 80s. His son, motivated by memories of his dad's unique bond and friendship with mine, and additionally prompted by the impending arrival of yet another anniversary of D-Day, scoured online Airborne association websites for information. He ran across a roster of some 513th PIR members which included some family names and locations, one of which listed me.

He remembered that Wayne had a son named Jeffrey in Virginia. He pored over a Northern Virginia White Pages and then simply took a chance with a random phone call Found me on the first try! We spent an hour and a half or more chatting, and have exchanged emails and photos, and I gained some amazing new perspective on my father's life and exponentially increased my awe and respect for him.

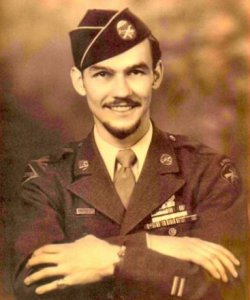

HECTOR AGUILUZ

|

WAYNE HYDE

|

--- Both circa 1945

Pop often told me how proud he was of being part of the Airborne, and the satisfaction he got from the rough camaraderie of his fellow paratroopers—but he said he always hoped I’d never have to experience the horror and loss of battle.

I remember going to see the movie “A BRIDGE TOO FAR” with him. He was really enjoying the film, and sat up straight as a scene depicted a bunch of old C-47s, loaded with paratroopers, taxied for takeoff. He was sort of fidgeting in his seat, moving around a bit, and he seemed to be adjusting his jacket or something. I leaned over and said

“Are you O.K.? What’s going on?”

”Oh, shit,” he said; “I’m getting nervous at take off, patting myself down to check my harness and find my ripcord. Force of habit. Goddam physical sense-memory, buddy. This movie’s very realistic; it’s THAT good..!”

Some years later I took him to see “SAVING PRIVATE RYAN”, and during a scene where the patrol headed by Tom Hanks is walking along through the countryside, they’re all talking back and forth. He seemed to be getting kind of restless, and I leaned over and said “What’s the matter, Pop?” He grumbled, “Those assholes shouldn’t be yammering to each other like that. Sound carries. Someone’s gonna get his ass shot off! Stupid bastards. No officer I ever knew would’ve allowed that!”

EMAIL

Drop me a note with any questions,

comments, criticism, cogent thoughts,

cease-and-desist orders, etc., etc...

|